The Early Surprise

We were looking at a very early start.

There was a brief silence during the group briefing, and I found myself thinking, “That’s a weird way to phrase it.” I already knew the scheduled start time was 3 a.m.—it was printed on the reservation, and customer service had confirmed it. The guide continued, “It’s going to be a very warm day tomorrow. Like today. And up there, it’s going to feel very warm, so we’ll be starting early.”

A Norwegian guy interjected, clearly confused: “Wait, wait—what do you mean by early?”

The guide smiled and said, “We’ll leave at 1:30 a.m. sharp from the trailhead. It’s just 15 minutes from here.”

Another silence fell. The guide filled it: “We have to leave early because of the sun. And likely melting conditions. The round trip will be about 15 hours.”

It was 5 p.m. I did the math. There wasn’t going to be much sleep.

The Foundation of the Trip

But I was thrilled. Genuinely excited, relieved, hopeful. A million things could still go wrong, but at least now there was a real chance that I—and the rest of the group—might make it to the summit of Hvannadalshnúkur. Just a few days ago, things had looked pretty bleak.

This climb was the very foundation of my Iceland trip. Months earlier, I’d contacted guiding companies, asking about conditions in mid-May. Eventually, about seven weeks before my trip, I took the leap and booked. No guarantees, of course, but I wanted to secure a spot.

My itinerary had some flexibility—about a week in case weather didn’t cooperate. What I hadn’t accounted for was the heavy snowfall Iceland received in the week before I arrived. Every day, I obsessively checked the weather. And when I finally landed, I was stunned: the forecast looked absolutely perfect.

The Booking Crisis

Then came the shock.

I reached out to the guiding company I had booked with just to confirm the climb for Wednesday. Their response? No one else had booked that day, so the tour might be canceled.

I was gutted. This was supposed to be a trusted, smaller operator with good reviews and personal service—not some tourist conveyor belt. Yet here I was, stuck in limbo.

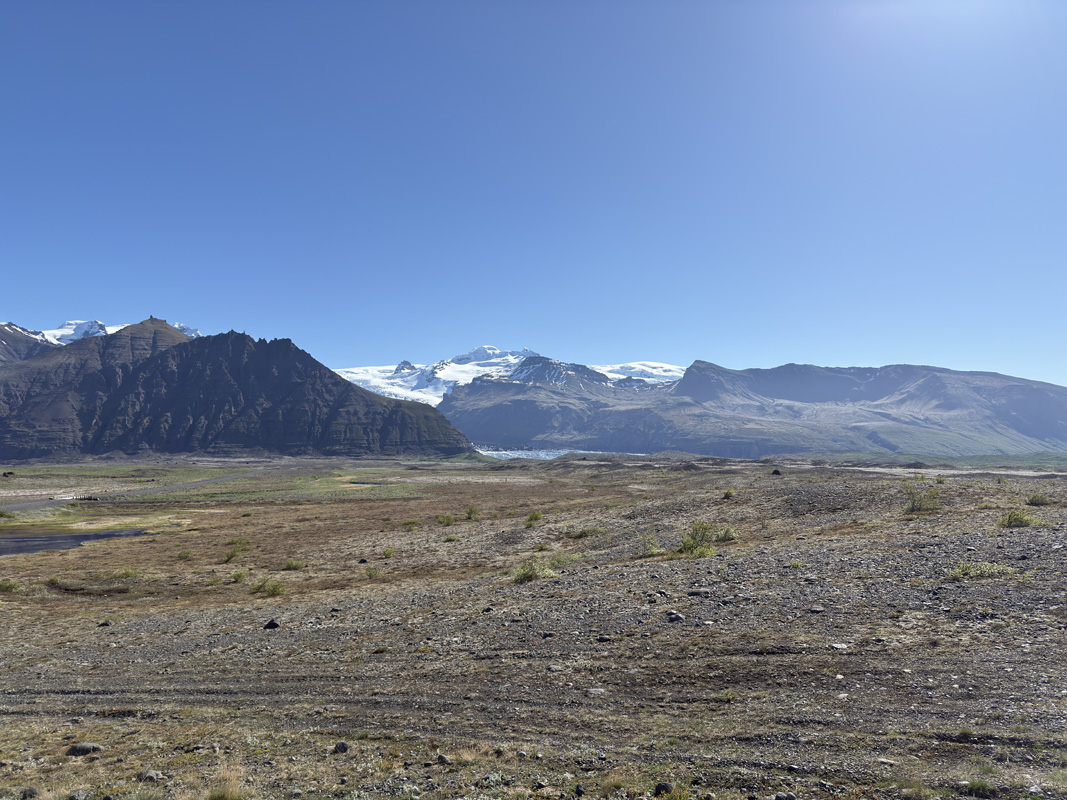

Tuesday came. I drove to Skaftafell as planned. It was afternoon. I followed up with the operator. Still no one else had signed up. They told me the trip was canceled. To do the climb safely, they needed at least two participants in addition to the guide.

I noticed their calendar had Thursday listed, too. I emailed to ask: were there any sign-ups for that day? No response.

I started to lose faith. This wasn’t just bad luck—it was poor communication. Why wasn’t I being updated? Why did I have to chase them? Shouldn’t they be helping me?

By late Tuesday, I was actively searching for alternatives. Somehow—miraculously—another company had an opening for Saturday. Their website had shown it as sold out, so I messaged them immediately. They had eight people booked and four spots left. I reserved mine within minutes.

It was a more mainstream operator, sure, but the reviews were solid, and they were responsive. I checked their cancellation policy: full refund if canceled more than 24 hours in advance. That gave me peace of mind.

Wednesday morning, the original company finally replied: we can wait until 2 p.m. to see if Thursday fills. Still no word about a refund. I was done. I packed up, left the campsite, and moved on. I wasn’t going to sit around on empty promises.

They never contacted me again.

Side note: I later watched a vlog by a young woman who had attempted the same climb. Her guide, from the same company, became ill during the hike, and the clients had to convince him to turn back. She didn’t name the company, but I recognized the exact email phrasing she mentioned—they had sent me the same one.

Luckily, I had booked through a third-party provider with a flexible cancellation policy and used a credit card. If needed, I could dispute the charge. But for now, I focused on exploring the easternmost point of mainland Iceland while waiting for Saturday.

The Group and the Gear

Friday afternoon came. I attended the pre-climb briefing. Fourteen people were in the group: Icelanders, Norwegians, Spaniards, Irish, Slovaks. The Irish guys were trying to summit every European peak—Hvannadalshnúkur was somewhere in the mid-20s for them.

We split into smaller groups. I ended up with the Irish climbers, who had serious technical gear. I felt a little out of place. What would they think if they knew I’d climbed Kebnekaise in sneakers and swimming shorts?

The guide wasn’t thrilled with my hiking shoes. “Too soft,” he said. I began to panic—this was my only pair. But it turned out one of the Irish guys had overkill boots and the company lent him another pair. My shoes passed.

I’m notoriously bad with layering. I often overdress. This time, I had prepped well—for colder conditions. But I really didn’t know what to expect at 2,000 meters. The guides stressed sunscreen. I’d forgotten to buy more. I had some, but would it be enough? I’d heard horror stories about snow glare. I also lacked a proper neck scarf. My backup was more suited to freezing temps.

There was a gas station 15 minutes away. No SPF 50, but I found SPF 30 and a thin scarf. Not perfect, but better than nothing.

The Night Before

Back at camp, I prepared everything—clothes, gear, food. The tent was up, but the midnight light made it hard to sleep. I got into bed before 10 p.m., but noisy neighbors laughed late into the night. Eventually, I retrieved my earplugs from the car and drifted off.

I had three alarms set—but didn’t need them. I woke 10 minutes early, adrenaline pumping. “Ready to rock and roll,” as the guide would later say. “Jolly good” was another of his favorites.

The Climb Begins

Everything was packed, but practical details still took time. It wasn’t fully dark—more like twilight. From the campsite, I could see the entire mountain ahead. I had to hustle. It was already 1:10 a.m., and I had a 15-minute drive.

Along the way, a thick fog bank appeared—visibility was near zero. Dangerous stuff. Not how I imagined the start.

At the trailhead, it looked like a sports event. Dozens of cars. Apparently, everyone had chosen the same time. The sense of scale hit me—our 14-person group wasn’t the only one climbing.

Adrenaline high, I awkwardly strapped on my harness—even though glacier gear wouldn’t be needed for hours. Crampons and ice axes were tricky to secure on my pack, but I managed.

The light was surreal—not day, not night. At 1:40 a.m., it wasn’t really either.

The Mountain Trail

The trail began with a steady uphill. Though we were warned there was no path, there clearly was—at least at first. For anyone used to hiking, the early section was easy. The main hazards were loose rocks and one exposed edge.

I was overjoyed to realize—for once—I had the perfect amount of clothing.

We climbed the west side of the mountain, so the sun remained hidden. Around 1,000 meters, the snow began. That’s also when I remembered: this was a volcano. The pumice stones were light and white—almost unreal.

Volcanic Origins

Öræfajökull is located just outside the main volcanic belt, stretching southwest to northeast. It’s connected to Snæfell and Esjufjöll. Much of its geology is hidden under Vatnajökull glacier. At 2,110 meters, its peak—Hvannadalshnúkur—is the highest in Iceland.

Öræfajökull has erupted only twice in 1,100 years. The 1362 eruption was the most explosive in Iceland’s history, producing about 10 km³ of ash. It devastated everything within 20 kilometers. The last eruption was in 1727. If you do the math… the 300-year interval is just about due.

On the Glacier

Before the glacier, we passed a bright yellow tent. I assumed they were mountaineers training for something extreme. Later, I learned they were skiers. Imagine skiing down Hvannadalshnúkur!

We roped up and donned crampons at the glacier. It suddenly felt serious. Dozens of climbers were around. Some even lacked crampons. Our guide reminded us what to do if he fell into a crevasse: “Do nothing—unless I say otherwise.” The risk was minimal today, thanks to perfect conditions.

Near the 1,800-meter plateau, the sun finally rose behind us. It was 7:30 a.m. For the first time, we saw the summit clearly.

Now it made sense: you couldn’t walk straight across the glacier. Cracks and crevasses were everywhere.

The Final Ascent

The final 300 meters was the hardest. The only steep section. But at the top—a crystal-clear, cloudless day—we had a full 360-degree view: Vatnajökull to the north, the Atlantic to the south, Mýrdalsjökull to the northwest.

This was the view I had dreamed about.

The Way Down

Descending was harder. The steep section demanded full attention. I even managed to puncture my pants with the spikes of my own crampons. The sun was now blazing. The snow glare was intense, but none of that really mattered. We had made it to the top of Iceland, and now it was only a matter of making it down in one piece.

One step at a time, the snow under our crampons became softer and softer. The guide recommended on the plateau that we could actually give up our crampons. But I felt it would be easier to walk down with them for extra traction. That was probably only psychological, with no real truth behind my choice. Walking in the sleet reminded me way too much of those snowy days in Stockholm and Helsinki. I recommended to my team members to keep going so we would reach solid ground as soon as possible.

When we made it back onto rocky terrain, it wasn’t fun either—my shoes and socks were completely wet after wading through the sleet.

The Finish Line

After 15 hours of up and down, we made it back to the starting point—the finish line. Our small group was the first to make it down before the rest of the 14 people total group.

At this moment, it was best to hand in the borrowed ice axe, crampons, and harness, and head for a shower. The guide and I had been discussing how nice it would be to have a dip in the sea, but I ended up just going back to the campsite to shower and change before heading somewhere for dinner—or lunch? How you want to phrase it.

While waiting for a burger at the same service station where I had bought sun cream less than 24 hours ago, I wondered whether the employee recognized me. I had been the one asking for SPF 50 sun cream—but they only had 30. I was clearly slightly tanned, if not a bit red after such a day. Did he have any clue I had been on top of the mountain that rose in all its glory from the terrace of this service station? Would people believe me if I told them where I’d been?

Even though I wasn’t physically or mentally exhausted after the day—and, to be frank, my feet survived without blisters—I fell asleep very soon. At sea level, just next to the highest peak Iceland has to offer.