At first glance, Hornøya might not seem all that remarkable, blending seamlessly with the surrounding landscape. But make no mistake—the surroundings themselves are nothing short of spectacular. Here, nature takes center stage, and you become a mere part of it. I’m hours away from the nearest urban center, hundreds of kilometers north of the Arctic Circle. This is as far northeast as you can drive in Scandinavia. The journey includes passing through Norway’s oldest subsea tunnel, the Vardøtunnel, which opened in 1982.

The tunnel leads to Vardøya Island, home to Vardø, Norway’s easternmost town. This town lies so far east that it’s even positioned east of Saint Petersburg, Kiev, and Istanbul—and as far north as Point Barrow in Alaska. Despite being in the same time zone as the rest of Norway, Vardø is more than an hour out of sync with daylight hours. But in July, none of that matters; the sun never sets.

I arrive early but choose to wait for the second boat to Hornøya, hoping the fog will lift while enjoying a quiet breakfast. A local Norwegian greets me and assures me that today is the perfect day for a visit. The temperature might even reach a pleasant 10°C, with mild winds to match. I chuckle to myself; my idea of a perfect summer day is clearly different, but this is the Barents Sea, after all. The climate here, once tundra, is now subarctic due to warming trends. Still, 10°C feels like a gift, given the area’s daily mean.

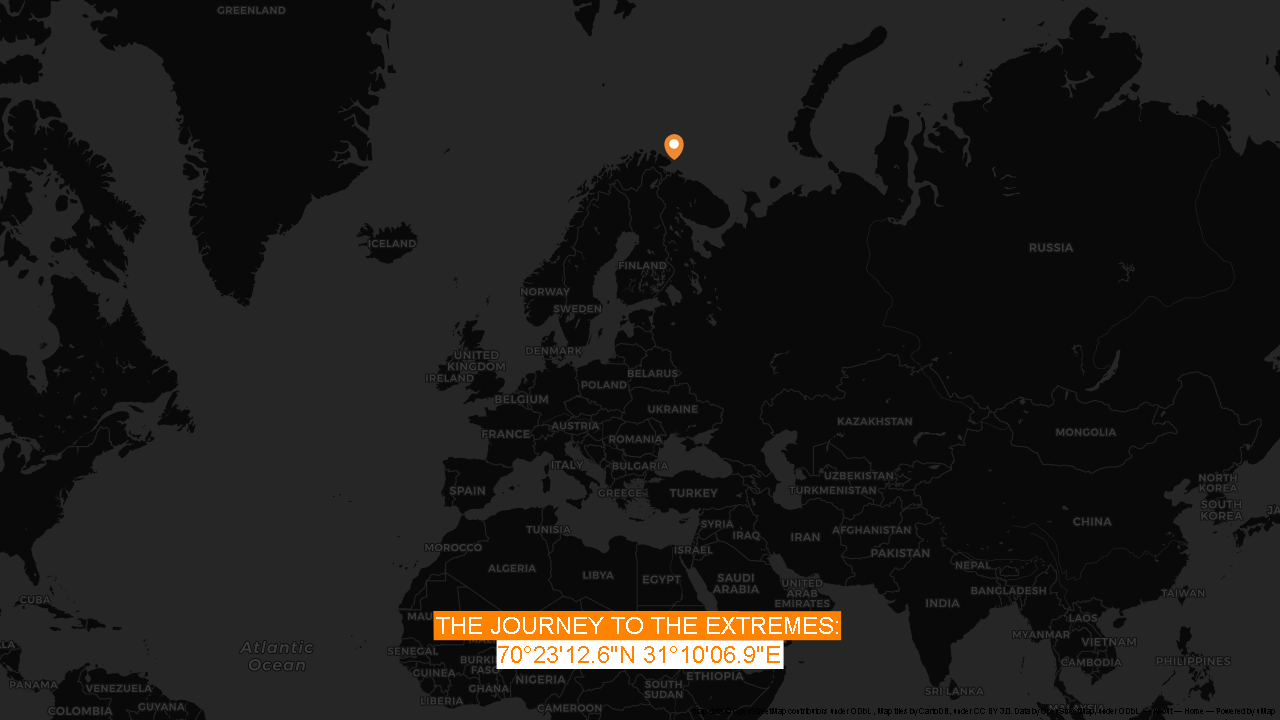

Hornøya lies just 1.5 kilometers northeast of Vardø. As I ponder the NOK 600 ticket price—wondering how profitable this must be for such a remote destination—the 10-minute boat ride quickly proves worth every kroner. From the distance, I spot a whale spouting water into the air. This alone would justify the cost. As the boat nears the island, the waves grow larger and the magic of Hornøya begins to unfold. This truly is the last stretch of Norwegian land before the vast expanse of the Barents Sea, at 70° north, 31° east.

The closer we get, the more awe-struck I become. Hornøya is home to over 80,000 seabirds, and the cacophony they create is indescribable. It’s an experience that must be felt, not just heard. As I step onto the island, I’m greeted by an overwhelming smell and the occasional bird dropping. Here, you’re the guest, and the birds make their presence known. If bird flu can spread to humans, this might be my moment.

The cliffs are nearly vertical, and birds are everywhere. It’s an awe-inspiring sight. Hornøya has been a nature reserve since 1983, and access is limited to a designated area between March 1st and August 15th. The marked trail up to the lighthouse can be slippery and muddy, but the effort is well worth it. Once past the challenging section, the terrain becomes more manageable, offering a chance to catch your breath and enjoy the fresh air. The surrounding waters are rich with fish, and soon, my patience is rewarded.

The bird noises are replaced by the occasional sight of a whale spouting water, setting off a game of cat and mouse as I try to capture the moment on camera. I find myself questioning whether this is real—everything feels so surreal.

I can’t tear myself away from the spot, but there’s more to discover on the island. At the summit stands Norway’s easternmost lighthouse, a 20-meter structure that has guided ships since 1896. It’s visible for up to 21 nautical miles (about 41 kilometers). Nearby, there’s a lighthouse keeper’s cottage where you can stay overnight. The island teems with wildlife: grey seals, white-beaked dolphins, minke whales, humpbacks, puffins, common guillemots, razorbills, European shags, and more. This tiny 0.4-square-kilometer island is a haven for nature lovers, and time seems to slip away as I explore.

Returning to the dock, reality sets in. Other tourists are waiting for the boat, and when it’s delayed, we’re informed that not everyone can fit into the small rubber boat that finally arrives. I wouldn’t mind staying longer, but without food or drink, that might not be the most comfortable option. After returning from the first ride, the boat’s driver, in good spirits, tells us that there’s a lot of whale activity today. “Anyone in a hurry?” he asks, offering to take us closer to the whales. I smile to myself, knowing that patience always pays off—and what a whale safari it turns into. Once again, I find myself speechless.

Later that evening, I reflect on the experience. I wish more people could visit, not just for the breathtaking sights, but to gain a deeper respect for nature. Yet, I know it wouldn’t be sustainable for the island’s true inhabitants, the birds, if tourism were more widespread. If you really want to visit Hornøya, you need to earn it. This is a place for those who can don a jacket, gloves, and beanie—even in the middle of summer.

One way or another, I know I’ll return to this extreme, unique corner of the world. Technically, I didn’t visit the easternmost point of mainland Norway, but I did reach the farthest accessible point. And that’s enough. Respect for nature comes first. Perhaps one day, outside of breeding season, I’ll have the opportunity to walk those final meters within the protected area.