Once again, I’m running late—not because I overslept, but because the schedules I create in my head are always far too ambitious. Still, despite the time crunch, I’ve finally made it to Birtavarre, the town where the infamous Fv333 road begins. Don’t worry if you’ve never heard of Fv333; it’s mainly famous among those who’ve driven it—or found themselves desperately seeking an alternative route to conquer Halti.

And I’m not exaggerating when I say the hike to Halti is one of the most renowned in Finland. The round trip covers 110 kilometers, usually taking most hikers between 5 to 7 days. That’s what led me to search for a shortcut in the first place. If helicopters or snowmobiles aren’t an option, the quickest route is via Fv333. I’d read plenty of online stories about people struggling on this road, but like most, I figured they were exaggerating. How tough could it be?

The Fv333 winds through Kåtfjorddalen valley towards the mountains. It starts as a regular asphalt road, but after about 10 kilometers, it turns into a rutted dirt track. Soon, I see signs warning of “privat anleggsvei,” but it’s not until a few kilometers later that the first real warning pops up: “Poor network coverage” and a suggestion to pay for parking in advance. A parking fee, in the middle of nowhere? But yes, it’s real.

The road seems well-traveled, though. It’s late afternoon, and I pass a steady stream of cars coming down. I later realize most haven’t gone all the way up to Guolasjávri. Gorsabrua, Northern Europe’s deepest canyon, is nearby, and one of the parking spots along the way is dedicated to hikers visiting it.

When you read about Fv333, you’ll hear stories of boulders blocking the road, sheep wandering aimlessly, and snow lingering until July. At one point, a sudden jolt from the road triggers my check brake warning light, and I break into a cold sweat. This is definitely not the place to have a puncture—or worse, brake failure.

I press on, eventually crossing a bridge where the road steepens, looking almost impassable—except for maybe a Land Rover. Giant boulders are strewn across the path, and the parking near the bridge seems far from Guolasjávri. It feels like the journey has only just begun, but the “road” ahead looks more like something for mountain goats than cars.

I ask a guy parked nearby for advice. He laughs, calling me a fool for even thinking of going further. After the bridge, he tells me, the road turns sharply right, though it’s nearly impossible to spot. He’s seen other cars coming from that direction, so I take his word for it. We both laugh at the insanity of trying to drive up what looks like a near-vertical disaster. He wishes me luck. I thank him for the advice.

Not long after, a Volkswagen Transporter with German plates starts tailgating me. Not exactly the kind of road you want someone riding your bumper on, especially as conditions worsen and there’s no way to let them pass. I know there’s no telling what lies beyond the next corner, but somehow, this all feels like part of the adventure.

The next 15 kilometers stretch on forever. The road is brutal, narrow, and winding. Every turn makes me hope I won’t meet oncoming traffic—because that would be a nightmare. Eventually, the Transporter finally manages to overtake me, and I can breathe a sigh of relief.

And yes, there’s no connectivity here. If anything went wrong, it’d be a disaster of a different kind. But the views? Absolutely stunning. If only I could relax and appreciate them. The ravine beside the road looks like it could swallow me whole. But if motorhomes have made it, I tell myself, then I can too.

The journey continues at a crawl. The road is battered by frost damage, melting snow, and rainwater erosion. Sometimes, there are large loose stones blocking the way. I cross one particularly terrifying wooden bridge where it’s safest to go one car at a time. There are few signs along the route, but when I reach a fenced area, I know I have to turn left and push on through some incredible mountain scenery. After passing the Red Cross cabin, only the final stretch remains.

The climb to 800 meters above sea level is challenging, but worth it. The parking at Guolasjávri is where the real ascent begins. I can only imagine how much more difficult this would be if there were snow on the ground—just another layer of chaos.

The weather is beautiful, maybe a bit too windy, but when you’re out here in the wilderness, you take what you get. I’m well-prepared with food and gear, though I realize I’ve done no research on the actual hike up Halti. With no connectivity, I’ll have to rely on the trail map at the parking lot.

I make the rookie mistake of walking on the wrong side of the reindeer fence, leading me straight into a sheer stone wall. With no way around, I crawl under the fence and take a shortcut through the reindeer pasture to catch up with the French family who came with the Transporter on the other side. They must know the way, right? When I catch up, I learn that the path is too steep for the kids, and one of the adults decides to turn back with them.

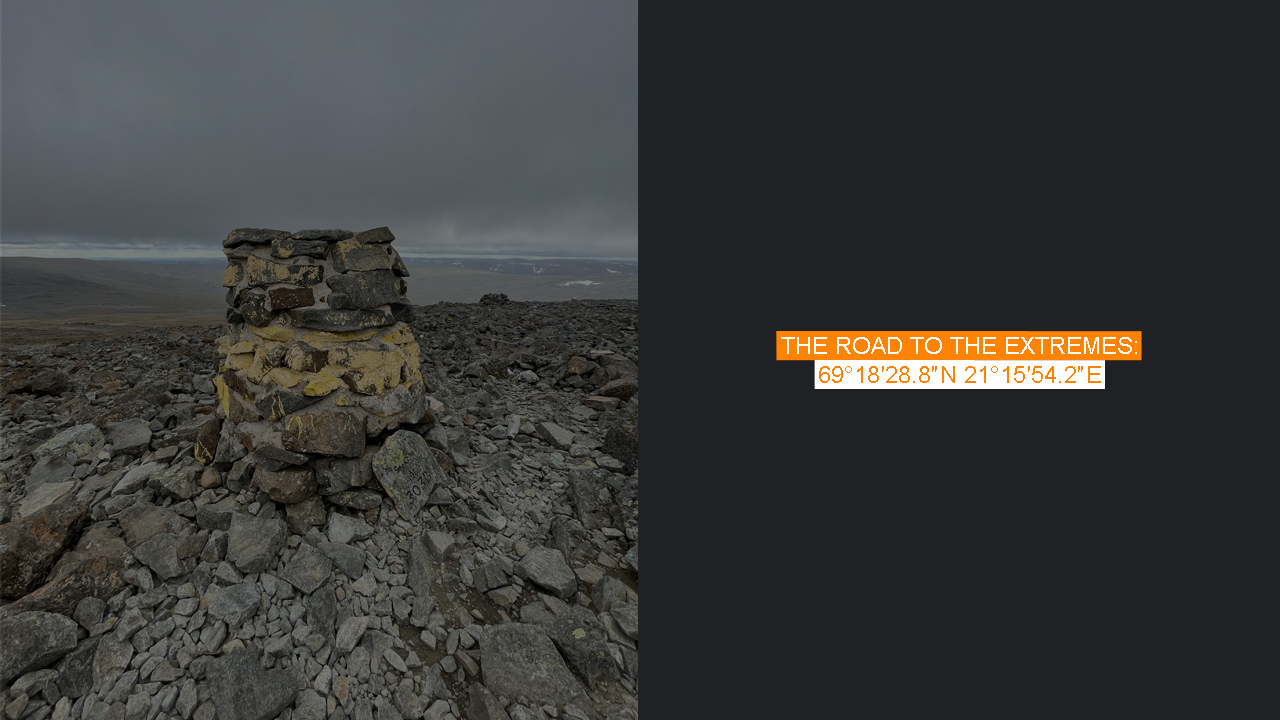

Along the way, I meet a couple coming down the path, followed by a group of Finnish women. We chat about the hike, and their advice gives me the confidence to continue. We all wonder where the red trail markers are supposed to be. All we’ve seen are piles of rocks stacked by other hikers. By now, I’ve already made it up the first steep section. The instructions are simple enough: From the parking lot, take the right side of the reindeer fence, climb the first steep section, then follow the left side when the view opens up. Soon, you’ll come to a small river, then climb steeply to the left, up to the right, and eventually reach Ráisduottarháldi, 1,361 meters above sea level—the highest point of Halti on the Norwegian side.

Norway had planned to give this peak to Finland to celebrate Finland’s independence in 2017, but bureaucracy got in the way.

From there, it’s just a few meters down to the peak of Finland, Háldičohkka. If you know where to look, the border marker 303 B is hard to miss. Writing my name in the guest book at the top felt surreal. The first book was placed there in 1933, and since then, over 200,000 people have signed it—that’s an impressive number.

Surprisingly, mobile service works at the top, so I send live photos to friends. A Tinder message pops up, leading to the most absurd dating conversation I’ve ever had. But that’s a story for another time.

Mother Nature, however, doesn’t appreciate my phone moment. The wind picks up, and soon fog rolls in, obscuring the views and making it difficult to navigate. Thankfully, I know the way back and can rely on the stone piles marking the route.

After 14 kilometers and six hours of scrambling over boulders, I finally made it back to the car—exhausted but relieved. But the journey isn’t over yet. I still need to make sure the car and I get down in one piece. I figure the late evening will be the safest time, with fewer hikers on the road. I clear some of the worst rocks off the first uphill section and begin my descent.

I know I’ll have to spend the night in the car—camping options are scarce. But once I hit the asphalt road again, the relief is overwhelming.