I had already tested sleeping in the two-seater Suzuki Jimny, and although I’d managed to make the setup work, it was far from ideal. Mostly, I was constantly worried about breaking something—especially since my excess waiver didn’t cover the car’s interior. That night, I made it to Reyðarfjörður, where the girl running the campsite chuckled at my makeshift sleeping arrangement. She had a point.

“You know,” she said, “since the weather’s supposed to be great for the next few days, why not just get a tent?”

I explained that I’d missed my chance back in Reykjavík. It wasn’t until later that I realized just how much worse the two-seater setup was compared to the four-seater. Still, I wasn’t exactly keen to backtrack just to get a tent. But she had an idea: there was a home and garden store about half an hour away that might have one.

They did. The only problem? It closed at 6 PM—and I was already too late.

I started doing the mental math. It was Wednesday evening. On Thursday, I planned to hike to the easternmost point of mainland Iceland, and on Friday, I needed to reach Skaftafell in time for my Saturday summit of Hvannadalshnúkur. If I didn’t get the tent tomorrow, I’d be stuck without one until at least Sunday evening—assuming the store was even open then. These are the kinds of problems you create for yourself. Even on vacation.

So I decided: go to bed early, wake up even earlier, and do the hike first. The store didn’t open until 10 AM anyway, and I could head back to Eskifjörður afterward. That meant hiking during the warmest hours of the day—with forecasts over 20°C—but I had no clue what to expect from the trail.

The Gerpir area, according to my research, is known for its dramatic coastal hikes. The route to the easternmost point was supposed to be just over 20 kilometers round-trip, with warnings that the road there required a proper 4×4.

Thankfully, I did wake up early. I reached Eskifjörður before 6 AM. From there, it was another 25 kilometers to Vöðlavík. The first half was an easy gravel road, but things got interesting when the road branched off and a sign pointed toward Vöðlavík. Another sign warned of poor mobile coverage and stated that the road was only suitable for 4x4s.

What could be more fun?

I had a lot of trust in my little Suzuki, but the tires weren’t made for this kind of terrain. The road climbed to around 400 meters before descending again, and the loose stones made it pretty sketchy. There were a few small river crossings that had me worried about the undercarriage, but hey—that’s what the Jimny was built for, right? The whole thing reminded me of my Halti adventures.

Eventually, I made it to Vöðlavík beach. To my surprise, one of the cottages in the valley had people staying in it, and a 4×4 camper was parked by the beach. Yet again, proof that no place is too remote for someone to show up. I began wondering how many visitors this place actually gets each year. Even Google Street View had made it down this road. Still—the beach opened like a secret: black sand, turquoise water, and wind-carved dunes that looked untouched by time.

I parked next to a small sign marking the trail: Vöðlar – Gerpisskarð – Sandvík, 5–6 hours, max height 670 meters. The sea looked tempting already, but I knew I had to earn it. I loaded my backpack with snacks and drinks, took a single hiking pole, snapped a photo of the trail sign (which also had a map), and set off.

The trail was well-marked with wooden poles—some topped with yellow, others with red. The sign mentioned both an old trail and a new one, but I simply followed the markers along the slope’s edge. At one point, the incline was so steep that one misstep could have sent me tumbling straight into the sea. There was no buffer zone to break the fall. Loose rocks made each step a careful calculation. Thankfully, the weather was perfect. A single rain shower would’ve made this twice as dangerous.

But the steep slope wasn’t the only challenge. I was soon facing one of my pre-trip concerns: snow. A large snow plateau stretched across the trail—clearly marked on the map—and the route went straight through it. I hesitated. I didn’t want to veer off-trail, especially since the terrain ahead looked even steeper and more unforgiving. So I made the ill-advised decision to believe the snow would hold my weight.

It didn’t.

Before I knew it, half my body was submerged. I couldn’t even feel the ground under my feet. I was suspended, my full weight on my elbows, and for a moment I panicked. No one knew I was here—only the parked Suzuki betrayed my presence. I cursed myself. Another rookie mistake—and I’d promised I was past that.

I scrambled out of the hole, shaken but unharmed. I had two options: left or right around the snowfield. I picked the left—naturally the harder one, as I realized on the descent when I took the other side. Still, I made it back to the trail. No more stupid decisions, I swore to myself.

The rest of the climb was a cocktail of grit and awe—each step hard-won, each view a reward. One particularly steep section was all loose rock, and I felt genuinely proud I hadn’t worn sneakers. Traction was everything.

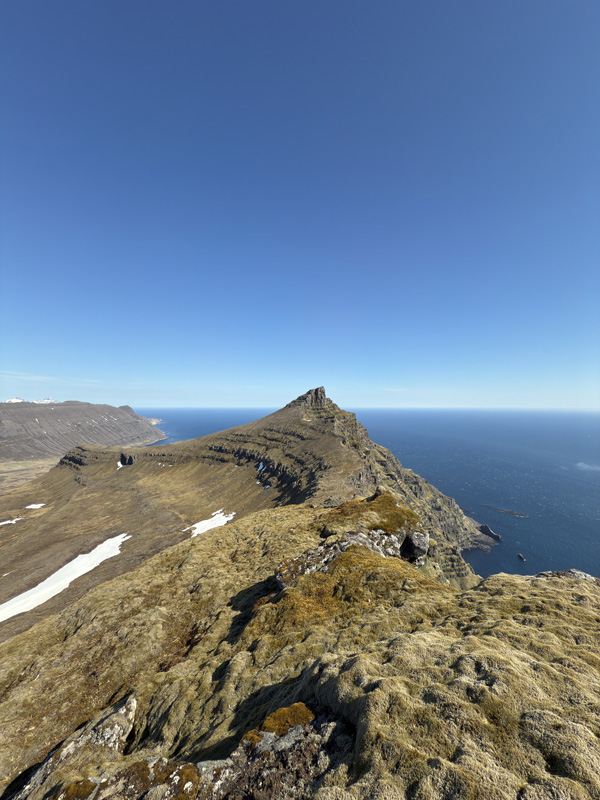

Eventually, I reached what I assume was the trail’s high point. Was it the 670-meter mark? Possibly. It wasn’t entirely clear which path was the old and which was the new, or whether you were meant to return the same way. Regardless, the views were staggering—north toward Sandvík and south back to Vöðlavík. I felt like I was on top of the world, a light breeze cooling the sweat on my forehead.

From there, I was hoping to follow the markings east toward the true goal—the easternmost point of mainland Iceland—but there were none. This section was surprisingly easy, almost flat, though the 400-meter cliff drop to my left was a constant reminder that I was still in serious terrain.

Checking my GPS, I realized that the absolute easternmost point was actually down at sea level—accessible only by boat or kayak. I considered it. Briefly. But climbing down a vertical cliff without gear (or sense) wasn’t happening today. Close enough, I told myself. The rest was just ego—or semantics, depending on your mood.

I lingered at the edge. Alone, completely. Not a soul in sight for kilometers. Only the gulls, circling protectively, concerned for their nests, perhaps.

Eventually, I turned around and followed the same route back—no more freestyling. I’d been as close as humanly (and safely) possible to the eastern edge of Iceland. One day, I’d have to return anyway—maybe to kayak to Hvalbakur, the easternmost island, some 40 kilometers offshore. But not today.

On the descent, I slipped once or twice, but nothing serious. It’s always a bit easier coming down, and that slight overconfidence creeps in. This time, I wisely went around the snowfield, figuring the sun had made it even softer.

Eventually, I made it down. I’d spotted two figures on the beach earlier and wondered if more people had arrived. But it was just the same 4×4 camper—still in the prime spot behind the dunes. A bit disappointing, if I’m honest. They’d taken the best location, and I respected their privacy by passing through the dunes to the beach.

Since I wanted some solitude myself, I walked toward the north corner of the beach. Not that it was necessary—the place stretched for 1.6 kilometers. The water was still cold, but the sand was warm, so I took off my flip-flops and walked barefoot. Of course, I immediately stepped on a sharp shell. It stung, and I worried for a moment—Hvannadalshnúkur was only days away. One wrong step could’ve ruined everything.

The drive back along Road 954 was mercifully quiet—no other cars, thankfully. I reached the top of the hill and saw a cargo ship returning from the Alcoa Fjarðaál smelter. A fitting sign that the day was winding down.

And yes—I made it back in time to buy the tent. With thirty minutes to spare, slightly sunburnt, limping, but smiling. Hvannadalshnúkur could come.